Classification of Technique:

1. Vacuum tube technique. (Tube excited by

Oudin or Tesla currents.)

2. Fulguration.

3. Constitutional (auto-condensation and auto-conduction).

4. Diathermy. (Direct D’Arsonval; electro-coagulation;

thermo-penetration.)

1. VACUUM TUBE TECHNIQUE.

This involves the use of the tubes by direct contact,

by effleuve (fine spray) and by actual sparks, from the mildest form to

the sharp caustic forms. It may be classified otherwise according

to its use as in (a) skin diseases, ulcers, inflammatory processes, etc.;

(b) relief of pain, as in neuralgias, etc.; (c) orificial application.

Vacuum tubes are employed where an essentially local effect

is desired.

Lubrication of Tubes. Any of the lubricating

jellies, unguents or cerates may be employed on tubes used within the urethra,

vagina or rectum.

Vaseline answers very well, for, although it is a non-conductor

of ordinary electricity, the thin coating required on these tubes is absolutely

no bar to high frequency currents.

Cautions. 1. As stated in Chapter V.,

high frequency currents are capable of producing annoying but not ordinarily

serious surface burns. These effects are especially quick to appear

when mucous surfaces are treated, as in rectal, vaginal, urethral or nasal

applications, and also in treating diseased areas about the lips.

On this account the application should be relatively short and mild if

a spark is employed in treating within the various orifices. Make

it a general rule never to allow a vacuum tube to remain in contact with

a mucous membrane for more than seven minutes at one treatment.

2. When the current is one of relatively high amperage,

the spark will set fire to any easily inflammable material. This

may be illustrated by lighting the gas with the spark, as previously referred

to. On this account care must be exercised in treating certain areas.

3. When introducing glass sounds into the male urethra

great care must be exercised not to use any undue force and thereby break

off the glass tube within the canal. These tubes are made of strong

glass, but may be broken by unusual pressure, or by a sudden jerk.

If difficult of introduction it is better to pass steel sounds first to

a size larger than the glass sound, as suggested in Chapter VII under Urethral

Technique.

Care of Vacuum Tubes. Asepsis. Although the

spark or effleuve from the vacuum tube is germicidal in character, still

it is the duty of the physician to use the utmost care and cleanliness

in employing it in order to guard against any possibility of spreading

infection from one patient to another.

In other words he would better follow some definite system

of sterilizing and disinfecting the tubes, and the nearer this is to surgical

asepsis the better.

Wiping off the tubes on a cloth or towel or simply rinsing

in water is not enough.

Apply the test to yourself. How would you like to

be treated with a tube that had been used in contact with a specific disease

and which had received no further cleaning than mere dipping in water and

then being wiped off with a towel that had already done similar service

an indefinite number of times?

Let your technique be so careful and conscientious that you

need never blame yourself for spreading contagion or infection of any kind.

This is a subject that I have not seen mentioned in any

treatises on high frequency currents.

Do not use the same tube for specific and non-specific

orificial cases. This alone will do much toward lessening the danger

of infection.

As these tubes bear heating, they may be sterilized by

boiling, just as surgical instruments are sterilized.

This, however, is not necessary, as immersion in strong

antiseptic solutions will be sufficient.

A tube that is to be used in contact with a mucous membrane,

such, for instance, as a vaginal or urethral electrode, should be immersed

in pure carbolic acid or in pure crethol, benetol or lysol, before again

using, if it has been in contact with the discharge from a specific disease.

In cases such as acne, psoriasis, eczema, neuralgia, non-specific

diseases of the urethra, rectum or vagina, etc., it will suffice if the

tube is immersed for a few moments, or kept permanently, when not in use,

in a strong solution of any one of the three antiseptics mentioned in the

preceding paragraph.

For this purpose a glass jar, large enough to take in

the various electrodes, should be filled with a twenty percent solution

of carbolic acid (a five per cent solution is not enough); or as its equivalent,

one of crethol, benetol or lysol containing a tablespoonful of either to

the pint of water.

An ideal way would be to have two jars, one containing

the full strength antiseptic, for the tubes employed in infectious cases,

and the other for those used in non-contagious diseases.

Personally I prefer crethol or lysol to carbolic acid,

because equally satisfactory and not caustic if any of the full strength

liquid accidentally comes in contact with the operator’s hands.

If the tubes are immersed in the pure antiseptic they

should be thoroughly rinsed in alcohol and water, or in water alone before

using. From the weaker solutions, water alone is necessary, but in

both cases hot water is preferable.

The conveniences of most of our modern office buildings

make the technique of sterilizing the tubes a simple one in the large cities,

but in smaller towns the physician will find it somewhat more of a task.

In the absence of large jars to keep the two solutions

in, with the tubes constantly immersed, wide mouthed bottles may be employed

for use before and after each treatment.

By sterilizing in this manner both before and after, the

tube not only receives a double sterilization, but also if it has been

taken care of immediately after use, if such a thing should happen that

it should be used again without remembering about sterilizing it, the danger

would be slight, and furthermore the tube is easier sterilized immediately

after using, than it is when the secretions or discharges have dried upon

it.

I have spoken of using the same care that you would with

a surgical instrument, although the danger with these tubes is not as great

as with surgical instruments for several reasons. In the first place,

they are not employed ordinarily in a fresh wound: secondly, the danger

is in carrying infection from one patient to another and not the additional

danger which accompanies a surgical operation, of infecting the wound from

the individual as well, and finally, in the majority of the cases treated

there is practically no serious danger of infection.

If one had a sufficient number of tubes it would be desirable

to keep an individual tube for each patient, which was used for no other.

Immersion in the weaker solutions referred to above and rinsing, or even

ordinary cleanliness would be sufficient; but at the close of the course

of treatments, before the tube was used for another case it then should

receive vigorous and thorough sterilization, in proportion to the danger

of infection involved in the case.

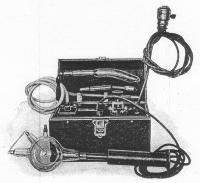

The sterilizer shown in Fig. 28 is an excellent one.

A basin of formalin solution keeps the tubes always sterile.

Some of my readers may think I am devoting too much space

to this subject, but it is an important one, and my early surgical training

has made me a “crank” on this point, and really, could you ever excuse

yourself if through your carelessness you spread, say a specific infection,

even in one single instance.

Measuring Dosage. One problem that confronts

the physician who is beginning to use the high frequency is a method of

measuring dosage. There is no meter which will measure the output

of the vacuum electrode, or in other words the unipolar current.

For auto-condensation and for diathermy the hot-wire meter is used and

proves relatively satisfactory. For the vacuum tube, in order to

convey an idea that would apply, no matter what size or make of apparatus

might be employed, I have made use of the length of spark which it is possible

to draw from the vacuum tube as a simple method of giving some idea of

the strength of current employed. This is a very crude method, and

open to some serious objections, but will answer the purpose in a general

way and convey a more intelligent idea than any method other than a meter.

With a definite amount of current passing through the

apparatus, there is a positive point near the tube that represents its

utmost sparking distance, that is, the longest spark that can be drawn

from that tube, and this will remain constant as long as the current is

constant – lessening the current shortens the spark; increasing it, lengthens

it. Therefore, if I say I employ for skin diseases a tube capable

of yielding a one-quarter inch or one-half inch spark, I give to the physician

a definite idea of the amount of current I would employ in the tube.

This does not take into consideration the sharpness of

the spark, which must be adjusted in accordance with individual susceptibility

and the type of machine used.

With the Tesla type of apparatus and particularly with

small machines, the spark is apt to be sharper in proportion, and is designated

frequently as a “hot” spark. With these outfits it is often impossible

to employ a spark more than a quarter of an inch in length. With

other types, a longer spark will be tolerated, and with the Oudin type

of apparatus we have what may be called a “cold” spark, and frequently

one three-quarters or an inch long may be more easily borne than a quarter-inch

“hot” spark. The cold spark is dehydratory and the hot spark caustic.

In interpreting my suggestions for dosage in Chapter VIII, these facts

should be taken into consideration. Ordinarily if the dose is given

one-fourth to one-half inch the first would be for the “hot” and the second

for the “cold” spark.

The Eberhart. Author’s Unit of Measurement for

Auto-Condensation. For a long time both physicians and manufacturers

have felt the need of a standard unit for measuring auto-condensation;

one that would fairly represent the auto-condensation output of any type

of machine. I believe I have solved this problem, and have a standard

of measurement that will prove acceptable to the manufacturers of any form

of apparatus. It will be found convenient for the manufacturer to

state with the directions for auto-condensation that the output of the

machine is so many Eberharts per minute to each 100 milliamperes registered

on the hot-wire meter. In this way with the dosage given as a certain

number of Eberharts, it is easy to note by the meter how many Eberharts

are passing per minute and by noting how many times this number will go

in the total dose stated the number of minutes required for the treatment

is ascertained.

There are three essential elements entering into auto-condensation.

First, the pressure or potential (voltage); second, the rate or meter reading

(amperage); and third, the time. When the voltage is high the amperage

is correspondingly low, and vice versa. In a general way the effectiveness

of any machine for auto-condensation may be expressed in terms representing

the product of the voltage and the meter reading (equivalent of amperage).

Thus 50,000 volts at 500 is the same as 25,000 volts at 1,000; each representing

an auto-condensation effectiveness of 25,000,000.

My unit of measurement for auto-condensation is based

on the passage of 1,000 volts at a rate of 100 milliamperes in one minute

of time. This unit I call the Eberhart and abbreviate it E.

We have two types of apparatus for auto-condensation,

the one high voltage and comparatively low amperage; the other low voltage

and high amperage. In a general way I assume that the first represents

a current of about 50,000 volts delivered at a rate of 350 to 500 milliamperes

as shown on a hot-wire meter. The second averages 25,000 volts, potential,

and is ordinarily delivered at a rate averaging 750 to 1,200; 1,000 being

a frequent rate. Applying our unit it will be seen that 50,000 volts

equal 50 E. For each 100 milliamperes meter reading, and if the meter read

500, there would be delivered 5 times 50 or 250 E. For each minute of time,

and this would give 2,500 E in a ten-minute treatment. With the other

machine 25,000 volts equal 25 E. Per 100, and with meter at 1,000 would

give 10 times 25 E. Or 250 E. Per minute, or 2,5000 E. Would require a

ten-minute treatment.

The manufacturer may state the voltage of his machine,

if desired, but the simpler way is to give the number of Eberharts to each

100 milliamperes meter reading. He should also state the average

meter reading at which the apparatus is to be operated. If he states

the voltage, to compute a required dose, multiply the meter reading by

the number of thousand volts, and divide this product by 100. This

is the number of Eberhart units being given per minute, and by dividing

the dose as given in Eberharts by this, we have the number of minutes required.

Going back to our previous example: to give 2,500 E. auto-condensation

on a machine of 50,000 volts with enough current passing to raise meter

to 500, multiply number of thousand volts, 50 by meter reading 500, and

product is 25,000. Divide by 100, which is done by cutting off two

ciphers, and we have 250, which is the number of Eberharts per minute–250

goes into 2,500 ten times, therefore it takes ten minutes to give the required

dose of 2,500 E.

It will be seen that it would be much simpler if the manufacturer

stated with this machine that the auto-condensation output was 50 Eberharts

per minute for each 100 milliamperes registered by the meter. Then

if the dose to be given is 2,500 E. And the meter registers 500, or five

times the 100 rate, it is easy to figure then that 500 is five times 50

or 250 E., and this goes in 2,500 ten times, therefore it takes ten minutes

to give that amount.

With the other type of machine we will say that the output

is 25 E. Per minute per 100 milliamperes; but this machine will ordinarily

be operated at about 1,000 milliamperes, or ten times 100, therefore it

is also delivering ten times 25 E. Or 250 E. per minute, and it will also

take ten minutes to give 2,500 E. In Chapter VIII the dosage of auto-condensation

will be stated in Eberharts.

It is well to remember that there is essentially no danger

in auto-condensation and therefore no over-dose, so that the dosage stated

may be greatly increased if results are not obtained.

The only cases in which caution is necessary, are those

where a patient is carrying a high temperature or where the pulse pressure

is 20 or lower.

Preparation of Patient. When the surface

of the body is to be treated, the question of removing the clothing arises.

If no spark is desired, the electrode must be in contact with the skin,

and any clothing covering the part must be removed.

All metal, such as chains, corset-steels, wire hairpins,

etc., with which the tube comes in contact or within sparking distance

of, will be charged with the current and give rise to sharp and disagreeable

sensations. If they cannot be avoided they should be removed.

Applications to the body, calling for a mild spark, may

be given through thin underclothing, or the patient stripped and covered

with a sheet, through which the spark is employed.

Aside from the reason spoken of above (chains, etc.),

when a sharp spark is required there is no especial need of removing the

clothing, in fact, a definite thickness insures a definite length of spark.

When the tube sticks on the skin, dust on talcum powder

or lay over the surface a very thin cloth, such as a handkerchief.

In vaginal treatments no disrobing is necessary.

General Technique in Skin Diseases and Surface Lesions.

In applying the high frequency spark over the surface of the body, as in

acne, eczema, etc., I employ a current of sufficient strength to produce

a spark one-quarter to three-quarters of an inch in length. The discharge

from the smaller Tesla coils is relatively sharper than from the resonator

or larger Tesla outfits, and a shorter spark is used, as the patient cannot

tolerate quite as much current in these instances. With a vacuum

electrode capable of delivering a spark of the length given, I do not try

to make use of the full length spark, but keep the tube in light contact

with the skin, thus giving a sufficient intensity of current, but avoiding

the pain that would result if the tube were held at full sparking distance

from the surface. The tube is passed rapidly back and forth over

the area treated, and this will be accomplished in the easiest manner by

holding the tube handle lightly with the fingers, with the thumb extended

along the handle. A side to side motion with the wrist will soon

become a matter of habit to the operator and the tube will pass lightly

over the surface without any sudden jerks or elevations to cause annoying

sparks.

If the skin is moist and the tube sticks, it may be dusted

with talcum or other dusting powder to obviate this difficulty. Another

method is to place a thin cloth over the surface, which will enable the

tube to be used smoothly and at the same time does not remove it far enough

from the surface to make an unpleasant spark.

Where itching is marked, the tube is raised from the skin

and as sharp a spark applied as the patient will tolerate for a short period

of time. This quickly relieves the itching and also quickly produces

the characteristic reaction of the current (hyperemia, etc.).

In treating epithelioma, lupus and any chronic ulcers,

a spark is employed in the same manner, that is, as sharp as the patient

can stand, but not for a long period, say from two to three up to occasionally

five minutes. Unless cauterization is sought, the tube should be

kept moving rapidly over the surface and not allowed to expend its full

effect steadily over any minute area. At the present time fulguration

(caustic) would be employed more frequently for epithelioma and lupus.

Technique for Relief of Pain. In congestive

headaches, neuralgias and other painful conditions, the beneficial action

of the high frequency current seems to be largely the result of counter-irritation.

Therefore, it makes very little difference whether a sharp spark is used

with the rapidly moving tube at full sparking distance, or whether with

the same intensity of current, the tube is kept in contact with the skin.

It depends upon the sensitiveness of the patient and also upon the location

of the area treated. A long sharp spark occasionally exerts a slight

caustic effect, and the surface will be covered with tiny blebs, which

are followed by minute scabs, making the skin sore and uncomfortable.

Unless the case to be treated is a severe one, it is not permissible to

push the treatment to this degree.

Cauterization. If a hot spark is held steadily

over the spot for from thirty seconds, up to two or three minutes, varying

with the patient, it will have a cauterizing effect. The reaction

is severe and the destruction of the tissue may be carried to a marked

degree. Such applications have been used in the treatment of warts,

moles, etc.

I have treated epitheliomas in this manner and have had

them separate from the surrounding tissue and peel out as smoothly as if

cut out with a die. It is too severe a measure, however, for the

average case. Fulguration involves the same principles, and is preferable.

The spark is derived from a metal point and anesthesia may be employed

if desired. The technique of this will be considered in another section.

Orificial Technique. The technique of the

application to the orifices of the body involves the use of tubes suited

to the various areas, and also involves the question of sterilization and

lubrication. In these cases the tube is in contact with the mucous

membrane and there is no sensation to the treatment except usually that

of warmth. There is in these cases greater danger of producing burns,

and the tube should seldom be left in contact for a longer period than

seven minutes at any single treatment. (See the section on vacuum

tube burns in Chapter V.) The technique is so peculiarly that of

the special organ involved that it will be given under its appropriate

heading in Chapter VII. It is desirable to remember that tubes should

always be inserted before the current is turned on, and the latter turned

off again before the tube is removed, thus avoiding all pain and shock

to the patient.

Cataphoresis. For cataphoresis a special

electrode is employed. See Fig. 29. The substance to be carried

into the tissues is in solution, and cotton gauze or felt wet in the solution

is placed in the depression on the face of the tube when the latter is

placed in contact with the desired area and the current passes for from

five to ten minutes or more as required. I caution against the use

of solutions containing alcohol or other inflammable substance because

of the danger of setting same afire with the current.

In one form an insulating ring prevents loss of current

and is a great improvement on the older style of tube.

See Chapter XII for special electrodes used by dentists.

Although strong claims have been made concerning the value

of high frequency currents for the purpose of carrying substances into

the tissues, I believe they are so far inferior to the galvanic current

for use for these purposes that they are entitled to comparatively little

consideration.

The principle upon which cataphoresis depends is the separating

of the particles (ions) composing the fluid by reason of the attraction

possessed for them by the poles of the battery; thus all positive elements

remain at or are drawn through the tissues toward the negative pole, and

vice-versa. Now, in using high frequency currents, which are alternating,

the attraction would be first in one direction and then in the other and

as a result practically nothing would be accomplished.

The claim is made that the high frequency current drives

substances into the tissues by “molecular bombardment.” I maintain,

however, that the cataphoric action of the high frequency current is too

feeble to commend it for general use, for which purpose nothing takes the

place of the galvanic current.

The use of dental electrodes for cataphoric purposes has

given good results. See Chapter X. It is really an electrical

diffusion, rather than true cataphoresis.

Bi-polar Tesla Technique. Ordinarily the

vacuum tube is attached to one pole of the Tesla outfit. In some

coils the sharpness of the spark is regulated by drawing off a certain

amount of the current from the active pole by bringing the sparking rod

near it, thus lessening the available current.

If it is desired to intensify the action of the Tesla

coil, the indifferent pole should be attached to the patient or grounded

by connecting to a gas or water pipe.

Selection of Most Suitable Form to Use. Where

a local effect is more essential, vacuum tubes, metal electrodes, etc.,

are employed, but if a systemic or constitutional effect is desired, auto-condensation

is to be selected, or the diathermic treatment may be used.

2. FULGURATION.

Fulguration. A long sharp spark for escharotic

or destructive purposes was employed for a long time by high frequency

operators, but the use of a metal electrode devised by Keating-Hart for

this purpose, which he termed fulguration, gave an unusual impetus to the

method.

Fulguration as employed at the present time may be considered

under two forms: 1. Caustic or hot fulguration, employed with D’Arsonval

or Tesla apparatus, and giving a hot, caustic or cauterizing spark.

The D’Arsonval fulguration is particularly suitable in orificial work,

such as papilloma of the bladder, etc. The Tesla is especially advantageous

in surface work, such as moles, warts and other superficial growths.

2. Dehydratory or cold fulguration, employed

with Oudin apparatus. The destruction of tissue is through a drying

process and there is no sloughing. There is essentially no pain,

but its range is necessarily limited.

Dr. W. F. Clark of Philadelphia employs a method of cold

fulguration with the static machine, to which he has applied the term dissication.

General Caustic Fulguration. The technique

which I employ for warts, moles and small growths is as follows:

The fulguration electrode is attached and the current

turned on gradually, while the length of spark from the metal point (Fig.

33), is tested by bringing the point nearly in contact with a piece of

metal, such as a coin. Without an anaesthetic it is impossible to

employ one more than one-thirty-second to one-eighth or occasionally three-sixteenths

of an inch in length. This spark is hot, and actually sears or burns

the tissue, as noted by the eye and usually by the odor.

It is not desirable to keep this spark in steady contact,

as it is too painful, but if the point is touched to the surface and quickly

brought away beyond sparking distance, the patient is better able to stand

it, and by a series of rapid sparks produced by a tapping motion of the

point, thorough fulguration my be achieved without unbearable pain to the

patient. Ordinarily I pass around the margin of the growth first,

and then fulgurate the center. It should be done thoroughly, and

the growth will present a brown, burned appearance. There is seldom

any hemorrhage, but usually some serious oozing. A crust or scab

forms which separates in a week or ten days (average eight), leaving no

scar. It is well to bear in mind that if you do not get it all off

the first time you can fulgurate again, but if you remove too much you

cannot place it back again.

For more extensive work, local or general anaesthesia

is necessary.

It is fair to state that very satisfactory caustic (hot)

fulguration may be accomplished with small machines.

In papillomata of the bladder, fulguration has been particularly

valuable.

Fulguration of Papillomata of Bladder. The

hot or caustic fulguration may be employed, using wire insulated with rubber

tubing, or the D’Arsonval method, which is bi-polar, may be used, as follows:

One terminal of the apparatus is connected to the fulguration wire, which

is passed through the cystoscope, and the other terminal is connected to

an indifferent flat metallic electrode placed on the abdomen. The

fulguration wire or electrode consists of a steel wire insulated with pure

gutta-percha. As this wire is to be passed through the channel of

an ordinary catheterizing cystoscope, it should not be larger in gauge

than No. 6 French.

The patient is prepared with green soap and water and

bichlorid, and the bladder distended with water. After the cystoscope

is introduced, the tumor is brought in view and the fulguration wire passed

through the catheter channel of the cystoscope until the end of the wire

is in view. The wire is then plunged into the tumor and the current

turned on. (Before introducing the wire into the cystoscope, cut

the wire so that the insulation is flush with the end of the wire.)

Just as soon as the high frequency current is turned on, bubbles (presumably

hydrogen) are seen emanating from the tumor. If the tumor is small,

or the electrode has been placed near the top of the tumor, an immediate

blanching of the tumor is seen. This treatment can readily be carried

out under the guidance of the eye, providing the insulation of the fulguration

wire is intact; unless the insulation is intact, a short-circuit in the

cystoscope and subsequent burning out of the cystoscope lamp may result.

After allowing the current to pass into the tumor for

about twelve to fifteen seconds, the current is shut off, the fulguration

wire withdrawn and re-applied to another part of the tumor. In large

tumors, this procedure can be repeated until many different areas of the

tumor have been treated in one sitting. As long as five or six minutes

may be consumed in one sitting. Naturally, the duration of each treatment

will depend on the size of the tumor. For example, in one case, one

sitting consisting of three 12-second applications was enough to completely

destroy a small papilloma.

As long as the intra-vesical electrode remains in contact

with the tumor no pain is experienced by the patient. When working

near the base of the tumor, or if the electrode comes in contact with the

bladder-wall, the patient frequently complains of pain. So that during

the first fulgurations there is no pain, whereas, toward the end f the

treatment, while working near the bladder in treating the remaining tags,

the patient at times complains of pain. It is also necessary to consider

the pain incident to cystoscopy. This is variable in different persons,

so that some of the patients cannot tolerate long sessions as well as others.

The number of treatments or sittings, as previously stated, is determined

by the size of the tumor, some cases requiring as many as six sittings.

Attention is called to the burning off of the insulation

near the end of the fulguration wire. After the current has been

turned on and the treatment carried on for a little while, sometimes only

ten seconds, the insulation becomes soft, and falls off or burns off from

the end of the wire, so that it becomes necessary to withdraw the wire

and cut the end off squarely. Unless this is done, there is danger

of the bare wire causing a short-circuit in the cystoscope.

Usually when the high frequency current is applied the

tissues become white and shrivel up. Sometimes the tumor surface

appears dark, as though it were baked. Not infrequently after an

application a larger or smaller piece of the tumor adheres to the end of

the fulguration wire. At other times these small pieces may be passed

at the next urination, and often they are obtained from the wash water.

These are carefully saved and examined microscopically.

It is suggested that papillomata should be considered

malignant in all cases; that in all cases of long standing cystitis which

has persisted even in the presence of careful treatment, or with the history

of frequent relapses, papilloma should be suspected, and the diagnosis

confirmed or contradicted by cystoscopy. It is the consensus of opinion

that the fulguration method is followed by remarkable results, but as yet

sufficient time has not elapsed for us to make a definite statement as

to an absolute guarantee that this treatment will prevent recurrences.

(Abstracted from an original article,

“Fulguration Treatment of Bladder Tumors,” by Herman L. Kretschmer, M. D., of Chicago. Illinois Medical Journal, April, 1913.)

3. CONSTITUTIONAL (AUTO-CONDENSATION AND AUTO-CONDUCTION).

Auto-conduction. In auto-conduction the patient

is placed within a large solenoid or coil, constituting a cage. The

patient is not in contact with this cage at any point and the high frequency

currents in the patient’s body are produced by conduction.

The cages are of several types, some in perpendicular

form, and others in a horizontal position. In the latter the patient

is either placed on a board which slides into the cage, or the top of the

latter is hinged like the cover of a basket. Some of the perpendicular

forms are collapsible, others are fitted with a door, the patient standing

or sitting on a stool.

Small cages are also made into which the arm or leg may

be introduced, thus producing localized auto-conduction effects.

The dosage is the same as with auto-condensation.

Owing to an inherent objection on the part of the human

race to being incarcerated in a cage, even for a short time, this method

of treatment, although excellent in results, is used comparatively little

at the present time; furthermore, it has no advantage over auto-condensation.

Auto-condensation. In auto-condensation,

one of the terminals of the apparatus is attached to the metal forming

one plate of a condenser and the other to the patient, who becomes in this

manner the other condenser plate.

The patient is insulated from the metal plate by silk floss,

rubber, mica, glass, or other form of dielectric.

In Figure 36 is shown a cross-section of a plate condenser.

In Figure 37 the body of a woman is substituted for the upper plate, thus

showing the principle involved in auto-condensation.

Auto-condensation is administered by means of a couch

or pad designed for the purpose and may include the whole body or be constructed

to influence only a part of it.

The original couch was in a form similar to that of a

Morris chair (Fig. 38), the plates of zinc being under the cushions on

back and seat, the cushions themselves being stuffed with silk floss or

with Spanish moss. The plates connect with one binding post of the

apparatus, and the other is connected to a rod from which wires run to

metal handles on each side, which are held by the patient, who receives

the charge whether one or both handles are grasped.

In that part of the circuit that is connected to the handles

a hot wire meter is placed to measure the dosage. No other form of

electrical treatment gives so high an amperage, except diathermy, the dose

running from 150 to 1,500 milliamperes, with occasional reports of the

use of even a stronger dose.

It is well to remember that there are two types of machines

used in producing auto-condensation. One has high voltage, but comparatively

low amperage, requires a cushion at least three inches thick and has great

penetration, so that a vacuum tube will light up within an area of several

feet surrounding the patient. With this type the average meter reading

to obtain satisfactory result is 350 to 500. It is seldom necessary

or desirable to secure a higher reading. Lower readings, 150 to 200,

would be used where it was desired to influence nutrition without particularly

lowering blood-pressure.

The other type machine has comparatively low voltage, but

high amperage. It may be used with a thin pad if desired. The

meter will read 750 to 1,000 on an average, and up to 1,200 or 1,500, according

to the potential of the apparatus. Auto-condensation is measured

in Eberharts, as stated in a preceding section in this chapter.

As long as the patient is in electrical contact with the

handles, that is, perfect contact, no sensation is felt except occasionally

a slight tingling or sensation of warmth. Sparks may be drawn from

the patient, and these may be quite painful. In type No. 1 a vacuum

tube held in operator’s hand will draw a spark from patient which is known

as one form of indirect spark. In general, a feeling of warmth pervades

the body after a few moments, and the temperature is shown by the clinical

thermometer to be from one-half to one degree higher than before the treatment.

The couch or cushion is connected to one terminal of the

apparatus, the patient to the other. The static machine with hyper-static

transformer does not give a sufficient amperage for the satisfactory operation

of a couch; neither does the average portable outfit, although the latter

has more amperage than the static machine. Both of these may be used

for charging small pads for restricted areas, and some types of the larger

portable coils I have found capable of operating a good-sized pad, if the

dielectric is thin.

In 1903 I designed the first portable body pad, which

folded together when not in use. It consisted essentially of the

top of the couch and was intended to save the space required for the latter.

About the same time Piffard produced a condenser pad for

the set of an ordinary chair (Fig 41)

It is a well-known fact that the thinner the di-electric

is, as long as it is a perfect di-electric, the greater the corresponding

charge that may be held on each layer of condenser. This caused me

to substitute flexible mica for the material used in the ordinary pad and

thus produce a portable auto-condensation pad only half an inch thick,

and capable of being slipped under the leather cushion of the ordinary

office treatment table, converting the latter into an auto-condensation

table. At the same time a much greater charge of electricity may

be condensed in the patient than with the thicker pads.

Pads less than three inches thick have been condemned

by the standardization committee of the American Electro-therapeutic Association,

therefore, at the present time I employ only the thick cushion.

Many ingenious operators construct their own chair or

couch, and from an article of mine on this subject in Popular Electricity,

November, 1909, I make a few excerpts:

“A glass slab, four or five feet in length, twenty inches

wide and about one inch thick, such as is used in a glass-topped operating

table, is fitted in a wooden frame and to the under surface is attached

a strip of zinc or of sheet lead 1/32 of an inch thick. This strip

should be about ten or twelve inches wide, so that when placed on the lower

surface of the glass it will leave a margin of about four or five inches

between the edge of the zinc and the edge of the glass. It should

extend lengthwise to within six inches of either end of the glass slab.

The zinc or lead plate is connected by an ordinary covered conducting wire

say, not smaller than No. 10 or 12, to one pole of the high frequency apparatus

and the patient connected by an ordinary metal electrode to the other pole.

The patient may be placed directly on the glass, but it is preferable to

place him on a thin cushion upon the glass, for sake of comfort.

“Another method is to take a wooden table long enough for

the patient to lie on and place underneath the table top a layer of plate

glass the full size of the top of the table with a strip of lead or zinc

attached to the under surface of this glass, always bearing in mind that

the essentials of an auto-condensation pad are to have a di-electric with

a layer of condenser below it, and the patient attached to the apparatus

to form the upper layer. Thus, an ordinary Morris chair or steamer-chair

may be used and a layer of lead or zinc fastened underneath the back and

seat of the chair, the two strips being fastened together with metallic

connections (chain or wire) and underneath the ordinary cushion of the

chair, four or five layers of rubber are placed to serve as the di-electric,

although the cushions themselves, if they remove the body beyond the sparking

distance of the charge on the zinc plate, would really make the air space

intervening serve as a di-electric. This is not as satisfactory as

when the layers of rubber are placed between. The patient then is

connected by the ordinary metallic hand electrode and conducting cord or

metallic handles may be fastened on the arms of the chair, the two connected

by a bifurcated conducting cord to the one pole, the zinc plates to the

other.

“Lastly, a pad may be constructed on the same plan as

the one which I have designed, using one or more layers of sheet mica large

enough to permit the body of the patient to rest on and making use of a

layer of condenser either lead or zinc underneath the mica, taking care

that it does not extend near enough to the edge of the mica to allow the

charge to leak over. On top of the mica place three or four layers

of felt or cover with leather as desired. Should the mica be insufficient

to prevent some sparking through, it may be obviated by placing another

thin cushion on top of this pad.”

The patient is placed on the couch or pad and connected

to the apparatus before the current is turned on, and then the current

turned off before the patient lets go of the handles, thus avoiding all

shock.

If the patient questions whether he is getting any current

or not a few sparks drawn from his body readily convinces him.

Another form of treatment which the patient feels to the

extent of strong muscular contractions may be made by introducing a spark-gap

into the patient’s circuit. This I describe in another section as

D’Arsonval surgings.

The value of auto-condensation depends upon its remarkable

effect upon general metabolism (see Chapter V). In nearly all cases

of hypertension the blood-pressure is lowered.

Auto-condensation treatments average ten to thirty minutes

in duration (2,500 to 7,500 Eberharts), and should be given daily, or six

times a week at first, in nearly all cases, gradually decreasing as improvement

takes place. Less than three treatments per week at the start are,

in my opinion, practically useless. Longer treatment may be given

if the physician desires.

Cautions. There is practically no danger

of an over-dose of auto-condensation, the only danger being in cases where

the patient has a high temperature that will be raised still higher, where

a small dose, if any, is given, and in case of a pulse pressure below 20.

See section Taking the Blood Pressure, and under Arterio-sclerosis, Chapter

VIII. In low pulse pressure there is danger of obliterating the pulse

by auto-condensation.

Author’s D’Arsonval Surgings. I have alluded

to the fact that placing a spark-gap in the patient’s circuit causes strong

muscular contractions. The similarity between this and static “surging”

caused me to apply the term of “D’Arsonval surging” to this form of treatment.

I first noticed it when adjusting the sliding rod on a

D’Arsonval-Oudin resonator. This rod enables the operator to balance

the current between the coarse solenoid and the resonator, or “tune” the

coil. Doing this with the patient on the auto-condensation couch

caused the latter to exclaim at the resulting muscular jerks.

I use a high-voltage, low-amperage type of machine with

a thick pad. Enough current is turned on to give a meter reading

of about 250 (125 E.). A vacuum electrode is held in the operator’s

hand and the length and strength of spark tested by touching the metal

handle which the patient is holding, before the tube is applied to the

patient’s body. The current is then raised or lowered to provide

a suitable intensity and length of spark, after which the electrode is

applied to the portion of the body to be treated. The spark is drawn

from the patient’s body, is disruptive in character, and is particularly

suitable for various skin diseases, having also the advantage of the patient’s

nutrition and general metabolism being benefitted by the auto-condensation

which accompanies it. In other words, it is both local and general

in its effects.

Taking the Blood Pressure. As a knowledge

of the patient’s blood pressure is vitally necessary to the physician using

high frequency currents it is important that he should have an instrument

for its rapid and accurate determination. The instrument used for

this purpose is called a sphygmomanometer and a number of satisfactory

machines are on the market. The diaphragm type is shown in Figs.

44 and 44b

The mercury type is shown in Fig. 44a. Its action

depends on opposing the pressure of a column of mercury with the pressure

of the blood in an artery. For this purpose the brachial artery,

in the arm above the elbow, is selected.

A cuff or band containing a rubber sack is fastened around

the arm above the elbow, with that part from which the rubber tube emerges

lying in front over the artery. Ordinarily the sleeve is rolled up

before the band is applied, but if the clothing is thin this is unnecessary.

A small rubber hose runs from the cuff to the machine, which has a U-shaped

tube containing mercury, with a gauge between. The zero mark on the

scale is placed on a level with the top of the mercury.

A rubber bulb is attached by a small tube to the machine,

and the physician holds this bulb in one hand, while with the other he

keeps a finger on the pulse in the patient’s wrist. The bulb is now

compressed and immediately air fills the cuff and the column of mercury

begins to rise. The operator continues to slowly inflate the cuff

until the pressure of the latter shuts off the blood in the brachial artery

and the pulse can no longer be felt at the wrist. When this occurs

the pressure of the column of mercury has balanced the pressure of the

blood in the artery and the reading on the scale opposite the top of the

column is the patient’s blood pressure.

In using the instrument it is customary to force the mercury

a little above the point where the pulse ceases to be felt and then wait

two or three seconds until the column settles to the point of the reappearance

of the pulse. By doing this one, two, or three times an absolutely

accurate reading may be depended on.

The scale reads from 0 to 300. The normal is 120.

The numbers refer to millimeters of mercury. A variation of 10 millimeters

up or down would not necessarily imply abnormal pressure, but 140 or more

would be presumptive of the presence of or tendency to arteriosclerosis.

Another instrument for accurately determining blood pressure

is the tycos diaphragm type of instrument, shown in Fig. 44.

This is not a mercury instrument, but the readings are

obtained by indirect, internal pressure on sensitive diaphragm chambers,

so sensitive indeed that every action of the heart is shown plainly by

the hand on the dial, as the hand works co-incidently with the heart.

With this instrument the observer can accurately determine

complete blood pressure, by that we mean maximal or systolic; minimal or

diastolic, and pulse pressure (the difference between the two). This

is not easy with a mercury instrument, because the great inertia of mercury

renders it difficult to obtain a diastolic pressure, for mercury requires

one and one-half seconds to recover itself, while in one second we have

had one and one-fourth heart impulses, so you can see that mercury does

not act quickly enough to accept the second impulse. Diastolic pressure

with a mercury machine may be obtained by the auscultatory method described

later on.

The minimal or diastolic pressure is fully as essential

as the maximal or systolic, for without an exact diastolic to subtract

from the systolic we cannot get the most important thing in blood pressure,

that is the pulse pressure, for by pulse pressure alone can it be determined

whether a pathological condition is compensated for or not.

The normal pulse pressure (difference between diastolic

and systolic) should be from 20 to 55 millimeters.

The determining of pulse pressure by those using the high

frequency current is absolutely essential, for, as said before, by this

we can tell whether a condition is compensated for, and whether the use

of high frequency current is indicated or contraindicated.

As an illustration, we will say that we have a case with

a systolic pressure of 170, and a diastolic pressure of 140. This

shows, by subtracting one from the other, that the pulse pressure is 30,

therefore normal. No matter then if the systolic be 170, for the

pulse pressure being normal shows that the condition is compensated (or

the pulse pressure could not be normal), and in these cases any further

reduction of systolic blood pressure must be accompanied by a corresponding

decrease in diastolic pressure or compensation will be interfered with.

Of course, if the systolic was reduced to 160 and the

diastolic remained 140, compensation would still exist, but would be at

its low limit, and the patient would probably not be as comfortable as

with 165 or 170, with 140 as the diastolic. If however, under auto-condensation

both systolic and diastolic pressures decreased, if not always the same

reduction, at least without the pulse pressure going below 20, the treatment

may be persisted in until the systolic pressure is normal.

Whenever the pulse pressure reaches 20 and stays there,

after carefully giving one to three additional treatments auto-condensation

should be abandoned. It has been carried as far as it can be of benefit

to the patient, no matter what the systolic pressure then may be, and I

would suggest spinal sparks to raise it slightly, that pulse pressure may

be at least 25.

Where the systolic reading is high it sometimes happens

that the pulse pressure will, when auto-condensation is employed, drop

to 20, or even 18, but after a few days the diastolic will reduce enough

to give an increased pulse pressure, and thereafter both systolic and diastolic

keep reducing in proportion, in which case the treatment is kept up.

See further discussion and examples under Arteriosclerosis, Chapter VIII.

There are two methods of determining blood pressure with

the tycos type, which I have taken from Dr. Cowing’s book, “Blood Pressure

Technique Simplified.”

First, the method of oscillation.

Place the bag over the arm with the two tubes well under

the arm and over the brachial artery. Wrap the remainder of the sleeve

around the arm much the same as you would apply a bandage, tucking at least

six inches of the sleeve under the last fold. Then place the sphygmomanometer

in one tube and the bulb in another and you are ready for reading.

Care should be taken not to put the sleeve on tight enough to cause any

apprehensive feeling in the patient. Place the fingers lightly over

the radial artery and send the pressure in the cuff up to the point where

the pulse disappears or is obliterated. This is the systolic or maximal

reading.

It is desirable that the patient’s wrist be supported

from below by the palm of the doctor’s hand, while the first and second

fingers lie with their tips over the artery. Thus the weight of the

hand is prevented from shutting off the pulse too soon.

Second, the method of auscultation. This is, by

far, the most practical method of accurately determining blood pressure,

as the dangers of personal equation are greatly lessened. See Fig.

44c.

Bare the arm, adjust the sleeve well up (as above described),

place the stethoscope over the brachial artery. Now gradually inflate

the bag, and the first and second sounds of the heart will become audible.

Increase the pressure in the bag to the point where all sounds cease.

At this point will be the exact systolic or maximal pressure.

Having obtained this, gradually release the air by means

of the valve, and the first and second sounds of the heart will become

apparent, increasing in volume as they approach the diastolic point, at

which point the second sound will entirely disappear.

The above method cannot be employed where aortic insufficiency

exists or where there is a dilatation of the vessels. These conditions

being observed, when the pressure is first increased on the brachial, as

soon as a slight pressure is placed on the artery, a pistol-shot tone is

heard, and will continue with but little variation throughout the observation.

When this condition exists it is absolutely necessary to resort to the

oscillatory method. It is also necessary to use the method by oscillation

when the pulse is feeble.

Having now accurately determined both systolic and diastolic

pressure, we compute the pulse pressure.

Pulse pressure is obtained by subtracting the diastolic

from the systolic, for example:

Systolic pressure, 120; diastolic pressure, 90; the difference,

pulse pressure, 30, and, as previously stated, it should not be less than

20, and would also indicate a pathological condition as probable if over

55.

In about 7,000 cases Cowing obtained the following average

normals:

Children from 10 to 17, 85 to 110 mm.

Adults from 21 to 40, 120 to 130 mm.

Adults from 40 to 50, 120 to 135 mm.

Adults from 50 to 60, 135 to 145 mm.

It is well to remember that there is an ever increasing

hardening of the arteries as one grows older, and a person of 65 or over

can very easily have a blood pressure of 160 and still be a comparatively

healthy individual. At the same time if these changes were not taking

place the blood pressure would remain the same, no matter what the age

of the patient might be. Female pressure is 10 mm. Lower than that

of males. Any blood pressures, however, between the ages of 21 and

50, lower than 100 or higher than 150,can safely be termed pathological

cases.

Leading life insurance companies now insist on the examiner

taking the blood pressure. Most of them reject applicants whose pressure

is 160 or higher, whether any other reason is apparent or not; just as

they do where the pulse is persistently above 90.

An easy method of keeping the range of blood pressure

in mind, which I have employed in my classes, is as follows:

Consider 120 the normal. At 20 above or below that

is 140 or 100, the warning signal is out, and at 20 more either way (160

or 80) the brink of the precipice has been reached and a pathological condition,

and probably a dangerous one, exists.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|